I. LANDFALL

“I’ve been walking around thinking, ‘I’m in day 40-plus of a hurricane.” Pine Knoll Shores police chief Ryan Thompson drives through his beach town under a warm spring sun—and it’s empty.

“It reminds me of six hours before landfall.”

As winter reached its end, the arrival in the U.S. of the 2019 novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, became an inevitability. It was a remarkably contagious virus that was spreading quickly across the globe. Still, the extent of the austerity it would impose on most of the world was not yet understood. Even with Europe undertaking shelter-in-place measures weeks ahead of time and in full view, the personal impacts of the situation were difficult to forecast. There was little historical perspective to place the circumstances within and glean some comprehension. On March 11, hundreds of attendees at the NC Main Street Conference exhausted the sanitizing supplies and formed lines to wash their hands, but still they mingled, ate together, and attended large sessions. On March 13, a national state of emergency was declared, and no events have happened since.

That’s not to say there weren’t preparations taking place. James Inman, city manager in Bessemer City, saw it coming and ordered hand sanitizer in bulk – an order that was cancelled by the supplier before arrival. Police chiefs began toying with the idea of altered schedules. Public works directors saw that multi-person garbage trucks posed problems as it related to the public’s collective effort to slow the spread the disease, otherwise known as social distancing. And if not voluntary, then soon forced upon everyone was a shift in attention from the future to the day-to-day.

But of course, cities and towns were already present in each of those temporal spaces, both handling the tasks of the moment and the strategy of the decade ahead. Cities and towns are many things. They are a sprawling urban hub and a mountainous retreat; they are quaint, large, developing, re-organizing, artistic, commercial. They are the constant provider—your roads, your water, your police. More palpably, they are where you grew up or moved to, and where you work and have a family, and where your neighbor has a family too. It’s this social aspect of towns that has come most clearly into view.

Standing in front of the Sylva library, renovated from an old courthouse and perched atop a hill that overlooks town, Mayor Lynda Sossamon sees a main street that had taken decades to progress from empty to buzzing—and is now back to empty again.

“It hurts my heart,” said Sossamon. She also highlights the positives that have emerged through the crisis: neighbors checking in on neighbors, and food being provided to residents in need. The lack of visible activity, though, is jarring. “We had so many businesses that were vibrant. Everybody was downtown. Now, it looks just like it did 30 years ago: empty and dead. I try to look towards the future, but will it ever be like it was before?”

Thread through every empty street or story of resiliency is the money. The lockdown, in regards to public health, saved innumerable lives, and through April, North Carolina had fewer than 10,000 confirmed cases, ranking 20th among US states despite having the ninth highest population. The trade-off is economical. The financial fallout of the pandemic has yet to be fully appreciated, and potentially will not be for months or years, due both to the delayed nature of data collection and the fluidity of the circumstances themselves. A few points are obvious. People are not outside and shops are not open, which means that fewer goods are being sold and less money is changing hands. Those transactions yield sales tax, a much-needed revenue source that accounts for 28 percent of the median operating budget in North Carolina municipalities. There’s also occupancy tax, collected through tourism and hotel stays, and that source of revenue has suffered even worse.

It will affect places in ways both different and similar. The two great economic calamities that have struck North Carolina in the past few decades are the exodus of the textile and manufacturing industry and the 2008 global financial crisis— downturns from which cities have responded and grown, but in varying ways and at varying speeds. Urban centers have thrived as the tech and financial sectors have found footing. Smaller towns have had to steer their communities more nimbly, often through sizable revitalization undertakings, to which many places have succeeded or are on the track to succeed. Still others continue to fend off the clouds of a recession that for them never quite parted. That North Carolina had grown at a stellar clip over the past 10 years does not mean that budgets were not always tight.

Through both those times and this one, cities have continued on. They cannot shut down. They cannot even pause, nor have they.

“The water has to flow,” said Inman.

By and large, the duties of the roles have only expanded, taking on both a bolstered version of their typical work, as well as a pressing and urgent responsibility to respond to the health crisis itself. Police forces and public works employees still do their daily tours. Downtown revivals tiptoe and sidestep ahead. Managers pore over upended budgets. Councils meet and make decisions. It’s on Zoom, it’s on weekends—it’s all still happening, across all hometowns, every day.

II. “WE’RE STILL GETTING THE JOB DONE”

Perhaps the two most visible components of a city’s operation are its police force and its public works service, and in no municipality statewide has either stopped.

That delivery, however—the officer responding to the emergency, the garbage truck rolling by the curb—is only the final mile of a process that has seen significant behind-thescenes reworking and reorganization since the onset of the pandemic.

Eric DeLaPena, the City of Charlotte’s deputy director of operations for solid waste services starts his day with hand sanitizer, gloves and a mask before floating through the administrative building to remind all others to do the same. It’s mostly empty anyway. Then, he figures out the logistics of socially distanced garbage pickup for a city with 223,000 curbside units, which require garbage, recycling, yard waste and bulky item collection; and 136,000 multi-family units, which means dumpsters or compactors.

His job has changed considerably in the past six weeks. Overseeing operations, much of his time last year was spent positioning the department for the future and considering how best to serve the ever-growing population of Charlotte, primarily through personnel and equipment issues. That has now all channeled into a day-to-day focus.

“Things have changed quite a bit,” said DeLaPena. “It’s permeated every part of our operation.”

Under a pandemic, everything is a re-allocation. Roles change and money is moved around. And though the same amount of employees remained on the job for Charlotte’s solid waste department, the utilization of that labor dramatically shifted.

There are a few ways to collect garbage, the main two being automated collections and rear load collections. They do not evenly fit into pandemic protocols. The automated trucks, because they can be one person to a truck, are significantly safer as it pertains to social distancing and the health of the employees. With the driver on the right side, the truck can pull up to the trash bin, operate an automatic arm, complete the collection process without requiring multiple operators or physical contact with the trash, and then can roll on to the next bin. With the rear load operators, those conveniences are not possible, so the process is altered. Bulky item and yard waste collection had to be suspended altogether.

Barbara Edgecombe, a veteran of the solid waste department, is not an automated collector, so is one of the employees most affected. There’s almost no part of the day that’s not impacted.

Schedules are staggered. She isn’t meeting up with her coworkers in the morning, and they aren’t heading out onto the route together. Some punch in at the warehouse, others at the fire logistics building across the street; some at 6:30am, others at 6:45. Separately, they load up on personal protective equipment, or PPE, for the day. Then, instead of heading out with three people in the truck, they head out alone. Once they’re on the route, an additional person is delivered to them, and will keep distanced by remaining on the back of the truck all day.

“We’re still getting the job done,” Edgecombe said of the new, twoperson arrangement. “They bring the person out, and then they come pick them up at the end of the day to bring them back in.”

Weekly automated collection is the most viable option, but to operate that arm is an art, says DeLaPena, and former rear load operators need time and space to train. Both were in short supply.

“Typically, we have four or five people, seven at most, in training at one time,” said DeLaPena. “The challenge to train this many people, all at one time, while social distancing, required a tremendous amount of acreage. Our normal training areas were not sufficient.”

To solve that problem, they partnered with local Bojangles’ Colliseum to host the training sessions. With events postponed or cancelled, the arena parking lot is now scattered with trucks and collectors in training.

Prior to the pandemic, the service requirements of the department had grown to match the growth of the city, and Brandi Williams, Charlotte’s solid waste community affairs manager, put a great deal of focus on behavioral communications—the small things that connected the community to the process, while improving effectiveness and efficiency of the service itself. Things like proper recycling and preparation.

“Now, it’s a lot less of that and a lot more making sure people are up to date on what’s happening, what’s going on,” Brandi said. “We’ve almost served as an additional customer service arm during this time.”

There are internal concerns, too. Operations are in-flux for a department that has 275 of its 310 employees in the field and not on email. Operations and decisionmaking at the moment require constant flexibility.

“How do we share this information? We can’t bring everyone in,” said Williams. “So, we’ve gotten creative in using the radio.”

Like every local government across the state, Charlotte’s revenue is frozen. Louie Moore is a business manager for the department, and sitting in a half-filled administrative building, reviewing numbers and revising the budget requests he had prepared to make, Moore sees plans for projects and new equipment fall apart under the weight of financial uncertainties.

“It’s a different world right now,” said Moore. “Charlotte has been expanding and growing so rapidly on the residential unit side, and we expect to keep growing. But when the revenue side is impacted, you get an imbalanced equation. That’s a problem.”

Still, the garbage is picked up. Completing her tours of duty one week and tours of training the next, Edgecombe even sees positives. Management has proven its ability to support its employees, and she’s taken notice. She’s learning more through the training sessions. She’s never short on PPE.

And, riding the streets, one person in the front and another on the back, she understands just how essential she is.

“The streets are empty, but people come to the door when we’re working and look out. Some try to give us high-fives, saying ‘Thank you, thank you—glad to see you.’ It’s a good feeling.”

It’s mostly empty in Carteret County, too. Chief Thompson’s tours of duty through Pine Knoll Shores

see little of the life one could expect to see on the Outer Banks on a warm April day. The streets and hotels are empty. Crime has gone down, and he’s impressed at the resourcefulness he’s observed of the community of 1,300—still, the amount of work has only increased.

It begins, as all pandemic tasks too, with a stockpiling of PPE. Communities around the state were all relying on the same outlets for material, as Thompson recalls, so while getting supplies in bulk was difficult, it was found. From there, Thompson took on several unofficial roles as they emerged.

“I feel more like I’m running a sanitation crew than a law enforcement agency,” said Thompson.

Chief Jeff Ledford followed a similar game plan in Shelby: acquire PPE, establish sanitation protocols, and do whatever necessary to maintain police service. Operationally, that meant segregating employees into “waves” so that different groups did not interact and risk contaminating one another, and then re-organizing officers into a “frontline” and reserve units termed “the bullpen.”

He worked concurrently with a local car servicer to have his crew’s police cars regularly sanitized, and a dry cleaning process was put in place at the station, so that officers could leave their potentially-infected uniforms behind. Ledford didn’t want anything going in with the family laundry.

“Today, I’ve dealt with dry cleaning and mental wellness,” said Ledford.

Law enforcement procedures do not neatly align with social distancing. Often, they’re in direct opposition, unable to work from home and, when in the field, applying the six-foot rule right up until they can’t anymore. In Bessemer City, Manager Inman, just hours after responding to a local emergency—a suicide—reports that rates for domestic disturbances and overdoses have risen. Back in Shelby, on top of it all, Ledford and city leadership were forced to begin their pandemic response while fending off a cyberattack that shut down several city systems.

But as Ledford describes, the duty to represent public safety is no longer just inherent in the job—it has become much of the job itself. In other words, it’s managing the anxiety of the community. That means prioritizing public visibility through a sustained level of service, at a time when it’s most difficult to do so.

“The one thing they need to see is their law enforcement out there on the line and to know that we’re here, we’re going to continue to stand that line,” said Ledford. “Across this state, people are doing the stay at home order and avoiding interactions and doing the things to keep themselves safe, and here’s a whole group of people that are putting it on the line, still, every day. It’s humbling.”

Still, operations have been stressed to the point of requiring revised processes. The only additional resource often available is extra hours from leadership. This was the conclusion both Ledford and Thompson reached, while also deciding that internal morale was critical. Officers needed to have a sense of consistency.

“We’re looking for those little things that we can do to help reduce the anxiety and reduce the stress,” said Ledford. “There’s been a lot of little things from a leadership standpoint to make their lives a little more normal.”

In Pine Knoll Shores, schedules were not revised, and additional shifts were taken up by supervisors. Thompson works seven days a week.

III. A REVIVAL, STALLED

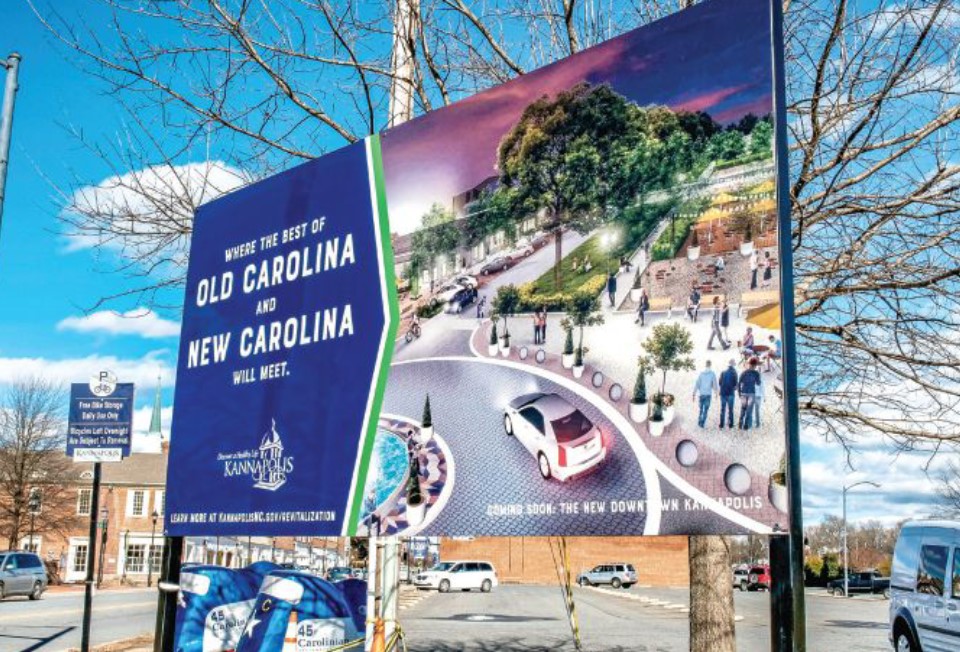

Summer in Kannapolis had expected to be one of gathering. Concerts downtown. A minor league baseball season. It was all built into its master plan.

City Manager Mike Legg drives through downtown Kannapolis, the site of his 15-year masterwork, which began following the textile exodus and was just days away from culminating in ‘Opening Day’ — a rebirth of town through a transformational, multi-phase revitalization project. The unveiling would be the first Kannapolis Cannon Ballers’s baseball game in the new stadium, Atrium Health Ballpark. It sits within redone streets, next to new apartment complexes and construction sites promising further success. Tenants had signed on, and businesses were moving in.

“Like clockwork it was coming together. It was the perfect plan,” Legg said.

The windows have ‘Coming Soon’ signs, and scattered around the area are a few joggers. Even empty, it’s a true renaissance from the uninspired area that emerged following two significant economic calamities. The lowpoint was in 2003 when Pillowtex declared bankruptcy and laid off more than 4,000 local employees. The single-tract economy in Kannapolis was from that point decimated. Another dip would then come with the economic downturn of 2008. Legg’s career in Kannapolis bookends the still in-the-works renaissance.

“Fortunately—or unfortunately— we’ve had to deal with this a few times,” said Legg. “Those cases were probably even worse, in some ways.”

Revitalizing Kannapolis became the goal the moment it cratered. It’s a common story across North Carolina, where towns and cities of all sizes are undergoing significant redevelopments, often spurred by the same catalyst—the departure of industry. In Hickory and Hillsborough, Wilson and Wilmington, stories abound. What sets Kannapolis apart is the approach and scale. The town began by purchasing its own downtown.

City leadership recognized the local potential. In town, at the abandoned Cannon Mills property, which had been sold by Dole Food mogul David Murdock in the mid- 1980s, was now the North Carolina Research Campus: a venture that includes research programs from eight UNC System universities. Development since its launch in 2008 had been slow, as had growth downtown. The vision, then, was that campus and downtown could be mechanisms of growth for one another, with the city’s role being to put things into motion.

Most crucial was the ownership situation of the downtown. Simply, it was all owned by Murdock. Kannapolis, opting in 2015 to pursue a direct role in the downtown’s development, acquired the entire, 84- acre downtown. “In a Bid to Revive Downtown, Kannapolis Buys Itself,” read the Charlotte Observer headline.

“At this scale, I would expect it’s never happened like this—to buy an entire downtown,” said Legg.

Enter March 2020, and the city’s work was about done. Everything was cresting with Opening Night and the start of the baseball season. The engine, from there, was community engagement. The engine was people downtown. The baseball season was the key. It was a planned celebration.

“Then we’re hit with a pandemic,” Legg said. “It’s a perfect, terrible storm.”

Precedented downturns and recessions were prepared for, so despite the unique nature of this situation, the finances won’t fall apart. Both Legg and Mayor Darryl Hinnant are reassuring on this point, though they expect a challenging situation both with the current budget cycle and the next. Rather, it’s the unprecedented social toll of the pandemic that most concerns them. It was designed to be a summer of gathering. If the economy can freeze, can the social nature of the city freeze too? It’s the cost of lost momentum.

“To have everything going in the right direction and we’re ready to celebrate together, and then ‘Oh, we can’t, stop, we have to just wait’ — that’s really painful. Socially, emotionally,” said Legg. Businesses that were ready to move into VIDA have put plans on hold. The hotel project downtown has also been paused. Legg expects it to take close to a year to get back up to speed. “That’s what my gut tells me.”

Under pandemic, efforts and focus don’t diminish. They re-allocate. As eyes temporarily turned away from downtown, attention instead turned to safety and community health, and a Cabarrus County taskforce was formed, containing representatives of the county, all municipalities within the county, and the local health system. Three times a week they meet, opening each time with details on the pandemic—number of cases, number of sick, and so on. And as the regular ways of socializing stop, others emerge. Mayor Hinnant, sitting on the task force, elevates the issue of mental health. “What can we do to promote the idea that it’s positive to call somebody up and let them know that you care about them? In the past, maybe we were so busy with our lives that we didn’t have the opportunity to do that.” Hinnant leads the way in that effort, connecting with neighbors, family members, and people across the community.

To Hinnant, momentum is only stalled. On the residential side of VIDA, interest in leasing apartments exceeds supply. People too, while distanced, are still coming downtown just to walk around.

“Occasionally, we’ll turn the (ballpark) lights on at night, just so people can ride by and see what it looks like with the lights on,” said Hinnant. “People can ride by and see the downtown all lit up and say, ‘Yeah, this is what it’s going to look like when we come over to the ballgame.’ We’re building anticipation to say, just bear with us, bear with us. It’s going to happen.”

And as the upcoming summer shifts, it still, in new ways, is meeting expectations. In parking lots, church leaders broadcasted service through FM radio waves, and divided by rolled-up windows, community members sat in their cars to worship together. Food services adapted, moving from community dinners to drive-thrus. One member of the community that had been socially isolated for months due to poor health called Hinnant to express his excitement about the new downtown, but really just to talk to someone. It’s becoming, as promised, a summer of gathering.

“This has been a gathering process. Gathering, and yet we couldn’t gather,” said Hinnant.

IV. “WE HAVEN’T BEEN DOING A LOT OF SLEEPING”

If only it was one crisis at a time.

Like the cybersecurity attack in Shelby, the storm of a pandemic does not preclude other storms, and in Charlotte’s case it was a literal storm. High winds and severe weather – tornadoes even, in some areas of the southeast – tore through Charlotte in early April, leaving behind a trail of tree branches just as the city reorganized its solid waste operations and moved to temporarily suspend yard waste pickup. The benefits of being a large, growing metropolis come with its tradeoffs, and one of them is flexibility. With resources split between short-staffed trucks and extra training sessions, re-implementing routes to collect the fallen debris was a logistical challenge. It took a full-department effort, including communications outreach from Williams, to organize a one-time city sweep to clean up the damage.

The storm presented dilemmas of internal safety as well. With potential tornadoes, how should the department take cover, while also staying six feet apart? What parts of the building can accommodate that?

“With every new question, the challenges are endless,” said DeLaPena. “My job has always been to keep employees safe while driving and operating heavy equipment. But now we have these additional risks. It just adds to the day-to-day priorities.”

Even when the problems are all pandemic-related, those problems are so multi-faceted and impact so many aspects of municipal operations that it’s an onslaught nonetheless. It’s a barrage on public safety, a barrage on the budgeting process, and a barrage on any semblance of a work-life balance. The duties of public safety and emergency management have latched onto nearly every position, all while the typical duties of that role have either continued on or even increased.

The heaviest load has been public well-being and employee safety. No one interviewed for this story did not mention this point first when asked about the current priorities of the town. Mayor Ian Baltutis in Burlington highlights their ability to limit the local COVID-19 case count, while being able to effectively route non-profit resources to citizens in need. Mayor Sossamon emphasizes the residents in Sylva—both children and adults—flocking to parking lots to use local businesses’ Wi-Fi, since their homes lack the reliable internet needed for work and school. Primarily via web calls, city councils across the state are making decisions daily to address these exact issues.

Manager Inman in Bessemer City senses a fear in town, towards both health and the economy. He manages it all. An admitted “worrier,” he acted early to supply his town with hand sanitizer, and when his order was cancelled, he led the town’s administrative staff to find it in bulk. They then purchased as many little plastic bottles as the local dollar store had in stock. “We’ve been filling them by hand.”

In the hours between preparing those bottles and attending online meetings, Inman faces a prospective budget that feels more uncertain by the day.

“I’ve been in local government for 34 years, and I don’t think I’ve had a more stressful 30 days.”

“This event is a simplifier,” says Rick Rocchetti, a local government consultant with a background both in management and organizational development. “The question is what’s going to be important now and going forward. I know what was important last month, but now, what’s up with all that?”

To evaluate those priorities, Rocchetti frames it in terms of cost. Having worked for the city of Raleigh for nearly 25 years, and with local governments since 1986, he’s intimately familiar with the structures and operations of municipalities. He’s familiar with the budgetary challenges.

“The short term piece is that North Carolina municipalities and counties will get through this. But I think that the cost will be high,” said Rocchetti. “The entire economic engine is stopped. Recovery from that is going to be a long-term thing.”

There’s then the emotional and organizational toll. How much of the burden is too much to bear? Like Chief Thompson in Pine Knoll Shores, the Joint Information Center in Cabarrus County, featuring Kannapolis Director of Communications and Marketing Annette Privette Keller, as well as communications professionals from the counties health department and other municipalities, were also on a seven-day-a-week schedule. “It’s exhausting. It’s overwhelming,” said Keller. “We haven’t been doing a lot of sleeping.”

There are similar stories of fulltime crisis responses statewide. It’s a bombardment of calls, meetings, extra shifts, and long weekends. Managers and directors walk this line delicately—a balance between employing the leadership skills required to navigate an organization through a crisis and becoming a shield that bears the full brunt of the trauma.

It’s an understandable impulse to become that buffer, Rocchetti acknowledges. But that line, while difficult to step, is critical to the long term health of an operation.

“Anxiety is a disabling thing,” said Rocchetti. “The long term cost is that it’s not going to help the organization be resilient… In the short term, we make decisions based on what we think. In the long run though, the consequence is health.”

Inevitably, though, the weight of the moment will fall near the top. Salisbury Mayor Karen Alexander took up the mantle when the number of coronavirus cases began to rise in town. Alexander, whose background is in architecture, employs a databased approach to her leadership, and she follows the numbers closely, even for issues that fall outside of her authority. She tracks the number of cases in town, and she knows how it has broken down demographically. She knows the mileage of broadband in town – 343 miles – with which the town and county can promote online learning and tele-medicine.

That research also allowed her to be one of the first leaders in Rowan County to understand the vulnerability of Salisbury’s nursing homes, especially the Citadel Salisbury—home to the state’s worst nursing home outbreak of COVID-19, as of the end of April. Adult care facilities are under the authority of NC Department of Health and Human Services’ county health departments, not the municipality, but she saw the numbers the facility was reporting and immediately was on the frontline.

“As Mayor of Salisbury, I need to know what is happening,” said Alexander, who coordinated with the city manager and police and fire departments to stockpile PPE for the affected facilities. “I’m responsible for protecting our citizens, even though it’s not my responsibility form a funding standpoint.”

In Dare County, the pandemic burden is shared by what Duck Mayor Don Kingston calls the “control group”—a collection consisting of the county commissioners, the six local mayors, the sheriff, superintendent, and a representative member from Hatteras Island. They’ve been meeting daily since mid-March.

Duck is eerily still. Spring is traditionally the time that property owners spruce up their homes for the heavy tourism season, but this year it is silence. That’s because the control group’s first decision was to declare a state of emergency, which allowed them to first restrict all visitation. Four days later, they went a step further and restricted all non-resident property owners. In the coastal, tourism-reliant areas of the state, the key to public safety was population control.

This event is a simplifier. While Kingston’s decision will have serious financial ramifications, the priority was public health.

“Our hospital has very limited capacity,” said Kingston. “We can deal with the normal summer population. But not when you’re dealing with the virus.”

V. COMMUNITY

Like the residents of Charlotte cheering on the garbage collectors and the police chiefs awestruck at the commitment of their officers, the coronavirus hurricane did not touch down in North Carolina without leaving a silver lined trail of charity and goodness. It is there, clear among wreckage both seen and unseen. It is a simplifying event. And it is a re-aollocation.

Stoneville was not going to layoff its parks and rec director Jackie Blackard, despite it being a part-time job, despite the parks being closed and financial worries bearing down. Instead of lose him, they opted to move him.

Town manager Lori Armstrong came up with an idea: a phone tree, or check-in program, where the town would call its residents to get an update on their wellbeing. Not only would it keep Blackard on staff, but it would establish a link to the community that would have been lost through the quarantine. That link was no small asset. Stoneville is the kind of town where residents go to city hall to pay their utility bills in person, not because it’s convenient, but because they can catch-up with the person at the window.

“We had to let them know we were still here,” said Armstrong.

At first, they considered calling everybody. The idea was then narrowed to only keep a line of communication with the local population most susceptible to the virus, and thus most likely to be quarantined for a long time. Blackard would call the town’s 55-and-older population once or twice a week, just for five or 10 minutes to chat. They got the numbers through the utility database. People that wanted to opt out could.

What’s resulted is a series of weekly phone calls looked forward to not just by the recipients, but by the caller, too. “I feel like I know them,” said Blackard.

“I feel like they know me. I told Lori, ‘Whenever this pandemic stops, we need to keep doing this.’ Some of these people, I’m the only person they talk to, maybe that whole week.”

Armstrong agrees—it will keep going—and has plans to evolve it from a pandemic check-in to an emergency check-in that will allow the town to help in case of future crises, such as if the power goes out on a citizen that relies on an oxygen machine.

At the beginning, Blackard opened each introductory call with a speech about who he was, and what Stoneville was doing. He added in a common, “and let me know if you need anything,” which led to stories both humorous (one resident jokingly asked Blackard to fetch him some pork and beans) and sincere (Blackard was able to secure a package of toilet paper for residents of an apartment complex that had run out.)

Most encouraging, Blackard recalls, is his most recent call: “I called her and she said, ‘I appreciate y’all calling so much. I love Stoneville,’” Blackard said.

“‘Well,’ I told her, ‘Stoneville loves you.’”