Facing issues head-on and with family in mind, the Cary Councilmember’s public service mindset was on full display this past year.

“This could be a really quiet year.”

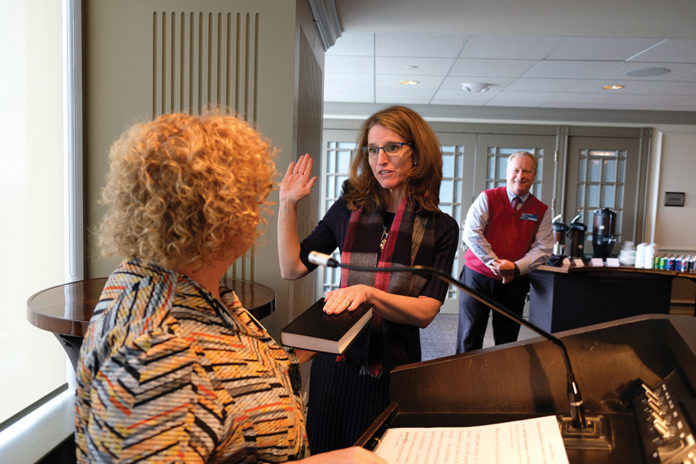

This is what Cary Councilmember Jennifer Robinson was told upon taking the NCLM Presidency in 2020, just at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in a prediction that turned out to be wildly incorrect. Rather, it was the early stages of a historically loud year, for both the state and nation alike.

The forecast failed for reasons both in and out of Robinson’s control. For the world at large, Robinson’s tenure tracked landscape-changing events. The day voting for the NCLM Board of Directors ended was the day Jennifer Robinson effectively became League President, and that was on May 25, 2020—the same day George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis. The weeks that followed featured what is believed to be the largest protest movement in American history, and the larger social movement has hardly diffused in the year since.

There is also COVID. Though Robinson took over with the pandemic underway, the impact was—and is still—developing politically, socially, and economically. Robinson was in charge when cities and towns desperately needed direct federal aid to support their communities, and she was in charge a year later when that aid was received. She oversaw stay-at-home guidance, then mask guidance, and finally, vaccine guidance. Then, elections. Recessions. A census. Waves and second waves and third waves of infections.

In her command, however, was an ability to maneuver. Robinson did so guiding both a statewide organization and the Town of Cary, where she’s served on the council for 22 years. She did so through an active approach. In the choice between simply bearing the terrible year quietly, and seeing the terrible year as a generational opportunity, Robinson chose the latter.

“I did not take this role to sit back and let it pass,” Robinson said. “On the whole, people will look back and say, ‘Wow, what a year of sacrifice and loss in our communities,’ and that is right. But with that being said, there were also some major benefits.”

It’s an approach Robinson has employed her entire professional life, and not always from a position of authority.

˘˘˘

The themes that pervade Robinson’s story are action and family. They’re present in almost every major chapter, including her move to North Carolina in the first place.

Robinson was born and raised in the suburbs of Washington DC, and began her career in that area. Over time, Robinson felt her and her family’s quality of life declining due to the rapid growth of the DC area, so she picked up and moved to Cary. About a year later, again facing the prospect of precipitous growth now in her new hometown, Robinson acted once more, this time as a citizen advocate.

She listened to her neighbors’ concerns about traffic, land use, home prices, and the many hurdles that accompany increasing populations, and she shared in those worries. It was not clear, though, who was voicing those concerns to a larger audience. So, on her own, she took them to council meetings personally as a representative for her neighborhood.

“I was here about a year when I started getting engaged by watching and attending council meetings,” Robinson said. “I was intrigued by the impact that our leaders had on the quality of life of our citizens.”

Her presence was noticed. A year or two later, as Robinson recalls, she was tapped to join a growth management taskforce, and then a short time afterwards, she was asked to submit her nomination for a vacant seat on the council. At the time, Robinson, who now works in town at the software company SAS, was running a small business doing data modeling, but the clientele was almost all private companies. Her proximity to Cary’s local government was all her own doing.

Here again, the central themes shine through. When deciding whether to move forward with pursuing a council seat, she leaned on the values instilled in her by her mother, Phyllis, a product of a coal mining family that, as Robinson said, taught her to “speak up for those that either could not or would not speak up for themselves.” That was coupled with civic-minded lessons from her father, Bill. Ultimately, she went forward, and was selected for the seat.

“I credit them for making me the person that would do this,” Robinson said.

Towards the end of her first two years, still working at her company and approaching her first election, Robinson and her husband Paul were expecting their third child. To better manage that limited time, Robinson decided to temporarily not accept any more contracts for her business until after the election, which she expected to lose. She won. It was the first of five successful elections for Robinson and the beginning of a 10-year period where she dedicated full-time hours to the role.

Robinson’s NCLM presidency began as her local government career started—by listening to concerns and taking them forward. She reached out to each member of the League board for a one-on-one call to hear the most pressing problems in each member’s community and to get their perspective on the key issues of the state as a whole. The calls were scheduled for 30 minutes. Many lasted hours. And each of those calls resulted in extensive notes, which Robinson kept and referenced continually.

“I wanted everyone, including those who were new, to feel like they were an integral member of a working board that was going to get something done,” Robinson. “It was important for me to get to know each individual and to hear from each person about what he or she was seeing.”

What resulted was a roadmap of concerns both specific and universal—issues as local as the moratorium of utility payment and as global as racial equity—that, in retrospect, serves as a travel log of the last 12 months. Robinson was guided not just by her own vision, but of an aggregate vision comprised of the visions of towns big and small—what she calls North Carolina’s “great breadth of diversity.”

She’s proud of many accomplishments achieved through the COVID era. Things as administrative as finding new ways to operate virtually, to things as momentous as the publishing of the League’s Racial Equity Task Force Report—the culmination of a months of work that will better support and accelerate cities and towns’ work on diversity, inclusion and equity. Additionally, she was central in the advocacy effort for cities and towns to receive financial support, which was realized in March with the passing of the federal American Rescue Plan.

“Although we experience similar challenges, those challenges have so many different nuances whether we’re a rural community or urban community, whether our economies are fueled by tourism or tech or so forth,” Robinson said. “For me personally, it was a year of enlightenment.”

Rather than some great balancing act, the interplay between her work and her family serve as complementing motives for Robinson. She notes that she is the only elected official in Cary history to have a child while serving in office—and she did it twice. Robinson also mentions that the initial recruiting pitch to get her on the council naively highlighted the minimum requirement: three meetings a month. She instead turned that into a two-decade engagement that has permeated her entire professional life.

“Everything you look at as you go through your community, you do through the lens of leadership,” Robinson said. “You look around and say, ‘This could be better,’ or you see a development and say, ‘We need a higher standard.”

“It’s so much more than a few meetings. It’s a way of life.”