Sylva, Webster, Dillsboro, and the rest of Jackson County have developed into one of the state’s premier destinations. In an area surrounded by beautiful towns and counties, how did their approach to tourism win out?

Sylva and the whole of Jackson County are enjoying a level of tourism unprecedented in their histories. Each year sees a precipitous rise in visitorship. Single months in 2020 outdo whole autumn seasons of less than a decade ago. This would be impressive under normal circumstances. For it to be happening in the middle of a pandemic—with a number of downtown destinations closed or at reduced capacity and with populations operating under safety precautions—is especially surprising.

Part of the success is natural: rivers and mountains playing host to fishing and hiking. The challenge of social distancing may actually serve as a benefit when trying to play up those widely-spaced activities. Still, that theory wouldn’t account for the six straight years of tourism growth before quarantine measures began in March. Nor would it explain the more than 10 percent year-over-year increase in four of the last five pre-pandemic years.

What led to this growth? The features in and around Sylva have been equally wondrous for decades. Many other towns tout similar attractions. What allowed Sylva, Webster, Dillsboro, and Jackson County to stand apart; to be able to not just economically withstand an otherwise-devastating pandemic, but to thrive within it? The answer is strategy and partnerships. Together, it is groundwork years in the making, and the turning point is a concept that flipped the traditional tourism approach on its head—one that prioritized place over patrons.

˘˘˘

A New Idea

Put into a single term, the strategy is placemaking.

Julie Metz, NCLM Associate Director of Business and Membership Development and former Downtown Development Director for the City of Goldsboro, understands the concept of placemaking well and described it as the following: “Placemaking is really all about making a place that people want to be. Somewhere they find themselves drawn to, that they enjoy spending time in, interacting with.”

Sylva Mayor Lynda Sossamon remembers the empty downtown of the 1980s and compares it now, when parking can sometimes be hard to come by, even in a pandemic. This shift towards placemaking laid the path for that evolution. The focus went internal. “Instead of just asking people to visit, we wanted to make Sylva a better place to live,” she said. That vision was formalized in the town’s 2017 economic development strategic plan, which reads: “Sylva, N.C., is a vibrant mountain town with an historic downtown that serves as a cultural and culinary center. Its natural beauty, proximity to trails and waterways, and distinctive sense of community make Sylva an ideal business location, a great place to visit, and a better place to call home.”

Nick Breedlove, Jackson County Tourism Development Authority (TDA) Executive Director and the former mayor of Webster, experienced that changing emphasis too. Once asked to almost exclusively work on advertising that invited people to come visit, his job now covers nearly every facet of the destination. “It has shifted over the years from destination marketing to destination management. What’s the experience like once you get here?” Breedlove said. “If your residents don’t visit your downtown, your visitors won’t either. You’ve got to instill local pride in your community within the residents and make them your advocates.”

Breedlove saw the newfound focus as part of an industry-wide shift. Sylva and Jackson County’s success is not in the invention, but rather in the embrace. Now relatively absent of advertising, the area, in many ways, speaks for itself. In many ways, too, it’s still speaking about the same things it always has: its natural resources.

The county’s slogan in the 1950s was, “In the middle of the most.” Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains and abutting Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the municipalities of Jackson County tout some of the country’s most exciting natural areas, which as compiled by the TDA include: one of the highest waterfalls east of the Rocky Mountains (Whitewater Falls, at 411 feet), one of the highest lakes east of the Rockies (Lake Glenville at 3,500 feet above sea level), a summit considered by some geologists to be the oldest mountain in the world (Whiteside Mountain at 390 to 460 million years old), and the largest box canyon east of the Rockies (Lonesome Valley).

“I looked back at a brochure of Jackson County from the 1920s,” Breedlove said, “and we’re promoting the same things we are today. Fly fishing, hiking, waterfalls.”

Still, there was untapped value in this resource. Unlocking it took creativity—“new angles on the same things,” Breedlove said. It also took partnerships, between the towns, the TDA, the Jackson County Chamber of Commerce, Western Carolina University, and other organizations. Through that collective engine, word of mouth propelled Jackson County’s reputation further than the reach of any billboard.

Julie Spiro is in her 21st year at the head of the Jackson County Chamber of Commerce, and has seen the crowd-sourced advertising firsthand. “People are telling other people,” she said about the area. “People are sharing their experiences, especially through social media and Instagram, posting those beautiful pictures of where they’re enjoying their life. It helps identify our area.”

The results are significant. Occupancy taxes collected from the last four full fiscal years beat the preceding four years by 24 percent. Just three months this year—July, August, and September—have already topped the entire 2012–13 fiscal year by more than 19 percent.

The results are significant. Occupancy taxes collected from the last four full fiscal years beat the preceding four years by 24 percent. Just three months this year—July, August, and September—have already topped the entire 2012–13 fiscal year by more than 19 percent.

Perhaps most astounding is the size and scope of the chief projects. There are many examples, some as massive as a downtown streetscape. Others are subtle, often boosting the collective reputation of the towns without as much as a passing notice: take-home stickers, branding, signage, and area-wide sustainability efforts. It’s this latter category that the local leaders highlight as the most important. They are not costly undertakings. Rather, they’re simply new ideas, reframing the assets already there.

“That’s the best part about placemaking,” Metz said. “It doesn’t have to be big, expensive infrastructure projects. I’ve seen $500,000 projects. I’ve also seen $50 projects.”

˘˘˘

The Strategy at Work

Two key projects illustrate this strategy towards both community and tourism-

based economic development. They’re both trail maps.

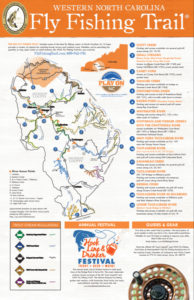

First, is the Western North Carolina Fly Fishing Trail, created in 2008 by Spiro. It was created out of economic devastation and, thus, as Spiro remembers it, necessity. The Great Smoky Mountain Railroad was a scenic tourist line had been a longtime economic driver for the area, especially in Dillsboro. That rail line ceased operations in 2006 and the local economy collapsed. Spiro estimated that 40 percent of retail shops in town went out of business.

“That made me super resourceful,” she said. “It caused us to look at everything we have available. What are our resources?”

What caught Spiro’s attention was the area’s most obvious asset: the natural environment, specifically the rivers and streams. Though advertised for centuries, she now looked closer. What was being offered? What made it specific and worth visiting as opposed to rivers and streams anywhere else in the country?

All it needed was a bit of packaging. The result was the nation’s first Fly Fishing Trail. Spiro led the effort to create a physical map that highlighted the prime fishing spots and different experiences the trail offered, and then published it. Twelve years later, it’s been featured in national publications like the New York Times and has been printed and handed out “hundreds of thousands of times,” as Breedlove estimates.

“Big rivers. Wide open spaces. Long, looping casts. Such are the popular images of fly-fishing, as it’s practiced out West…But in the creek-laced mountains of western North Carolina, with several thousand miles of public and private trout water packed into a million acres, there’s another version of the sport,” a New York Times piece from 2009 on the Fly Fishing Trail reads.

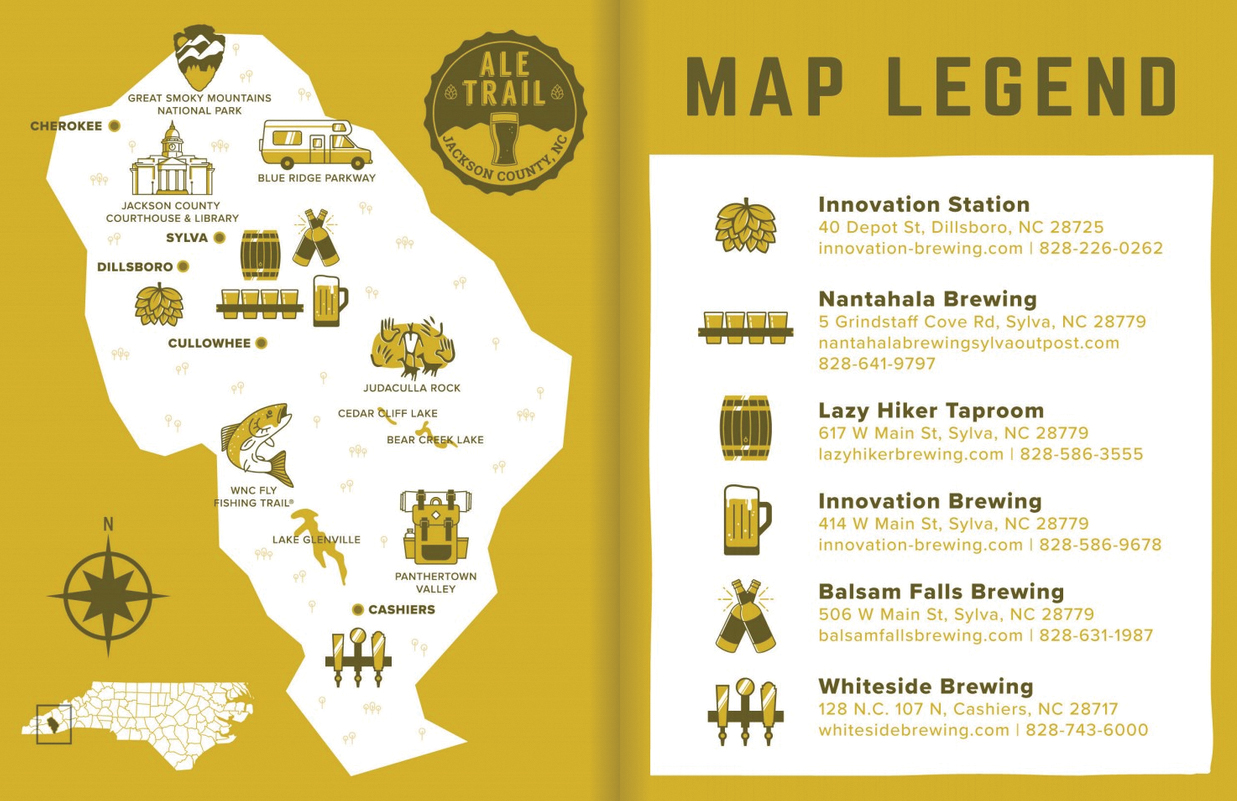

The second example follows almost an identical playbook, albeit on land. It’s the Ale Trail, or Jackson County Brewery Trail. Though not trademarked like its fly fishing brethren, its successful packaging of a somewhat common resource—in this case, breweries—is the same.

This project, formalized by Breedlove and facilitated by the towns, was essentially created by the community itself—a true testament to local pride and the creative environment created by the town and county leaders. Breedlove tells the story of seeing a woman in 2018 walking down Mill Street in Sylva with a hiking stick. When asked whether she had trekked off the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, she said no. Rather, she was trekking the mile between a brewery in Dillsboro to a brewery in Sylva. “I thought, ‘Every small town in North Carolina has a brewery now. But what do you do when you have four just along your Main Street corridor, and two more in neighboring towns?’” remembers Breedlove. “There has to be a way to turn these into an asset for the towns—a way that captures them collectively and brands them as something.”

Immediately after, he engaged the towns and began working with the county’s partners in public relations and advertising. Soon, the Ale Trail was born. Maps were created that not just highlighted the area’s top beers on tap and the route to get to them, but effectively cross promoted other attractions in the area too. “Hopefully it extends their stay and leaves them with a good experience,” Breedlove said. “It’s nice to be at the brewery, see visitors come through, look at your collateral and put it in their purse.”

Add in the hiking and waterfalls map, diligent conservation efforts, Sylva’s “secret season” (also known as winter) and a dozen other projects, and the sum is larger than its parts. People, as the numbers bear out, want to come back. Since 2015, tourism spending has increased over $30 million. By making it lovely for their residents, they’ve made it especially lovely and worthwhile for the visitors.

“It’s not a one-time thing,” Sylva Mayor Sossamon says of the attractions. It’s part of their appeal. The main strip of Sylva is less than four square miles, and yet one trip to the area only scratches the surface. “The Ale Trail takes multiple visits. The fishing trail takes multiple visits. Every trip to Sylva can be different.”

˘˘˘

The Engine

In evaluating the successes of the area, every person interviewed for this case study independently indicated the strength of the local partnerships as the pivotal factor. It is the consensus asset in how Sylva and Jackson County have been able to edge their tourism economy ahead of similarly attractive areas. The partnership aspect is so strong, in fact, that credit for each project is difficult to attribute. The lines of project ownership, development, and support are blurred, beneficially and without ego.

“We are all working together,” Spiro says. “It is not a competition. It is truly for the betterment of everybody.”

The municipalities’ roles blend in as well, though some individual responsibilities do emerge. First, the towns, especially county chair Sylva, facilitates those partnerships and serves as their main hub. It is through Sylva that associations like Main Street contribute to the process; it’s where county-focused leaders like Breedlove and Spiro are based. And second, the towns, as the builders of infrastructure, take on a significant part in solving logistical problems. The Town of Webster serves as a prime example. Mayor Tracy Rodes discusses the Fly Fishing Trail and the tremendous amount of attention it has brought to the streams. Visitors, economic development, and town pride are all increasing. Parking availability, however, has diminished. “We have done such a good job of getting the word out, that when everyone comes, you realize you have infrastructure needs,” Rodes said. With space limited and future road construction already scheduled to restrict needed routes, there is no easy solution. Still, being in the town and understanding the community, she doesn’t just pinpoint the problem, she contextualizes it. Then, she sends it back into the partnership apparatus where a variety of support and funding sources will begin tackling the problem quickly and efficiently, as they have in the past. “The need is identified and shared.”

It’s an arrangement that works, and the benefits speak for themselves, Mayor Sossamon says, keeping the low points of Sylva’s history front of mind. Just a few decades ago, downtown closed at 5 p.m. Those were times defined by silos—an arrangement that, considering the environment and assets at play, don’t make much sense. Still, that was the status quo. And though she doesn’t point to a specific moment in which that situation changed, she can look back, compare, and see the clarity in their current approach.

“After all,” she said, “we’re in the mountains. Visitors don’t care about town and county lines.”