Elizabeth City started the Historic Building Showcase, and Tarboro formalized it. Now, the format promises to boost towns’ rehabilitation efforts statewide.

Launched by one municipality and successfully replicated by a second, Historic Building Showcases seemed like a golden ticket before being halted by the pandemic. Targeting and developing North Carolina downtowns across the state, they were a win-win scenario for communities and cities alike.

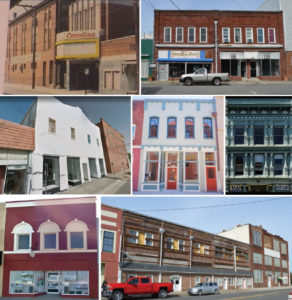

It is nothing new for state and local leaders to hone in on old vacant and underutilized buildings. Their value to the community is known, as are the reasons they sit unsold or unattended. The difference with these events was the format—the confluence of all relevant and prospective parties, and a piece-by-piece addressing of the hurdles that afflict this process. What resulted was significant momentum. Buildings that had sat empty were suddenly bought up. The number of interested buyers increased overnight. Longtime local blemishes saw the lights turn back on.

Though temporarily derailed, the energy created by these events has not diffused. Rather, their appeal has only grown, seen now not only from a perspective of economic development, but also economic recovery. It started in Elizabeth City.

˘˘˘

What Does an Empty Building Cost?

The cause of vacant historic buildings in a city’s downtown area varies, though across North Carolina there are a few prominent culprits. Sometimes families move, or there are simply absentee owners. Other times, much larger economic forces are at play, as tobacco warehouses and old shops become skeletons of companies that once flourished. The brick and mortar serve as memorials. Their impact on the town, however, never really subsides, because once built it’s either a blight or a benefit.

The price of an empty building is in many ways an opportunity cost. What could be there that is not? Picture one of North Carolina’s many revitalized Main Streets, and you’re given a scene flush with both culture and commerce. The heritage of the buildings—brick, repurposed, neatly representing both decades past and now—cannot be separated from the business happening in and around them, nor vice versa. It is a package deal that creates a city center, and these buildings play a central role. Having those vacant leaves that central role empty.

A State Historic Preservation Office (HPO) team in collaboration with local partners spearheaded these showcases and oversees many initiatives that strike at this very problem.

“It does a lot to people’s sense of community and belonging,” said Ramona Bartos, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer with the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. “You experienced that building, it’s a landmark in your mind, and it says it’s a source of pride in the community. I think too, especially when something gets transformed, it’s a sense of, ‘Wow, look at that. Did you know that was behind those walls?’”

Elizabeth City understood that missing value too. The efforts began with city leadership, and they were quickly partnering with the Restoration Branch of the State Historical Preservation Office (SHPO). Deborah Malenfant, executive director of Elizabeth City Downtown and a department head for the municipality, and Kellen Long, a planner with the city, soon took the reins. Having a deep understanding of the local situation, they were able to work with Bartos to organize an event that would specifically hit on the town’s areas of need.

The goal, put plainly, is that vacant properties get put to use. The need involves the matchmaking of a buyer, a seller, and a contractor. Complicating the issue, however, are the guidelines—and incentives—surrounding historic properties. There are sizable financial motivations. There are also strict rules to follow. Several key challenges are created in this environment, and though not every town’s situation is identical, some main themes persist: hesitant buyers, lack of network, and lack of local support.

All of those hurdles affected Elizabeth City. Worst among them was the deficient network of contractors. They were fortunate to have a number of historic properties for sale, and they had several interested buyers. However, not enough local construction companies had experience in renovating these types of buildings, which created a backlog of projects. With supply stagnated, demand rose and cost did as well. Soon, the prospective buyers were priced out of the business.

“Someone would come in, see a historic property, get super excited about it, put together a plan, and then they’d find that the construction costs were 30 to 40 percent higher than they had budgeted,” Malenfant said. “It was creating a really significant bottleneck.”

“Someone would come in, see a historic property, get super excited about it, put together a plan, and then they’d find that the construction costs were 30 to 40 percent higher than they had budgeted,” Malenfant said. “It was creating a really significant bottleneck.”

The other issue, which is especially pressing in other communities, is the trepidation of the buyer as it pertains to the tax incentives and, more specifically, the requirements for receiving those incentives.

Buyers of buildings listed in the National Register of Historic Places can restore those buildings and receive significant reimbursements through tax credits. To achieve those funds, the investor must abide by a certain set of federal regulations during the rehabilitation process. For many people, this is an area where they have no experience. HPO staff members work year-round to combat the ensuing uncertainty, and host a dozen workshops each year on the tax incentive process.

“What we try to do is shepherd people through the process and also demystify the process for them,” Bartos said. What must be followed are the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, and as Bartos describes them, they boil down to guidelines on how to transition a building from one purpose to another, while respecting the historical nature of the structure. A tobacco warehouse is not going to handle the tobacco market anymore, but it could become an apartment complex, or a mill, or some other commercial venture. The standards aim to respect the building’s authenticity and heritage.

“They’re not onerous,” Bartos said of the standards. “They should not be scary. They actually help enhance projects.”

On the federal level, if the project will be income producing (as opposed to a homeowner property), investors receive a 20 percent tax credit for each dollar invested into the rehabilitation. North Carolina’s Historic Preservation tax credits offer an additional 15 percent on top of that return, with another potential 10 percent return depending on what county the project is located within and what purpose the rehabilitated building will serve.

With the challenges of buyer and builder pointedly felt, and with the other challenges understood, Malenfant, Long, and Elizabeth City set about organizing their Historic Building Showcase.

The Agenda

The city introduced the day with remarks from Mayor Bettie J. Parker and Assistant City Manager Angela Cole, then went into a session titled “Why Invest in Elizabeth City,” which was hosted by the local director of economic development. Just by virtue of hosting the event at all, one potential challenge was immediately addressed—that of local support—and this portion of the program hammered that sentiment of assistance home. The City put itself out there with a clear message: your success is our success.

“It showed that our city administration and government placed an importance on this type of project, and that we were going to be a support network, not a bureaucratic system to maneuver through,” Malenfant said. “I think it changed the perception and enabled people to take a breath and say, ‘Alright, the city is on board with this, so I think we can make it happen.’”

They were speaking to approximately 50 attendees, some of whom were interested buyers, and the rest a purposeful group of architects, builders, and contractors. No specific section of the agenda had been dedicated to this challenge. Yet, by assembling the right group, networking the needed parties became easy.

“We were going for quality over quantity,” Malenfant said. “We didn’t exclude anyone who wanted to be there, but the intent wasn’t just to do tours of cool old buildings. It was to do a very specific approach to recruit people to invest and restore these buildings.”

Long recalls event organizers at one point almost having to force attendees to stop talking. “These weren’t general conversations,” she said. “They were seriously talking about project ideas, very specific, and very detailed.” Even before getting to the crux of the Showcase, the backlog that had stymied Elizabeth City’s historic rehabilitation efforts began to be relieved. “It blew up the bottleneck we were struggling with. It partnered people with resources across the state and even into Virginia.”

Next, the educational portion of the Showcase began: three presentations, all focusing on the tax credits. An architect, who had led numerous historic preservation and adaptive reuse projects, began with a session on the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, and a property investor who is also a board member for Preservation North Carolina finished the early portion of the day with “Tax Credit Financial Structure 101.” Bartos spoke in between and provided an overview of potential projects. Malenfant and Long received emails afterwards from attendees letting them know how informative they found those events.

Finally, the actual Showcase began. Elizabeth City and HPO staff targeted five potential projects to tour and scheduled a look at an already-underway tax credit rehabilitation project that had been successfully progressing. The tours took a total of three hours. Attendees saw these five properties in a setting that encouraged creativity and brought out ideas with each additional revealed detail. Then, to gift wrap the experience, they walked through an ongoing project that made the prospect seem all-the-more real.

“Often, they cannot even conceptualize how to make it happen,” Long said. “So, we showed them. ‘Here are the successes, and here’s how you can do it.’ The balance between success and how-to was a strong component of this.”

Within a few months, three of the five properties had sold and were working with HPO. A fourth, which garnered the most immediate interest, was under contract before the deal fell through due to COVID-19, though interest remains high. Malenfant is quick to note that these were not hot properties beforehand. In fact, they had almost no interest.

From an Idea to a Model

One of the attendees in Elizabeth City was Tina Parker, the Main Street coordinator in Tarboro. Parker had independently thought up a similar idea—some way to generate interest in the local downtown buildings that needed rehabilitation. She discussed the idea internally and found out from a colleague that Elizabeth City had scheduled something that closely resembled her idea. This was April 2019, the same week as the Historic Building Showcase taking place 90 miles east.

“I called Elizabeth City and asked if I could shadow the event for the day,” Parker said. “So, I took off for the day and visited.” Parker saw how Elizabeth City had laid out the Showcase and addressed the main obstacles that historic preservation efforts face. She also saw the tools that SPHO brought to bear. “It occurred to me that we could definitely do it. No questions asked.”

Again, the planning began in the municipality, and again the HPO partnered with the city to host the event in September that same year. Parker noted what would translate well to Tarboro, and what may need tweaking. Ultimately, with roughly the same design (including a presentation from the same architect that spoke in Elizabeth City), 45 attendees enjoyed similarly informative sessions, networking opportunities, and tours.

Created by Elizabeth City and then formalized by Tarboro, this idea had now become a model that could travel. That’s not to say there are not significant organizing efforts still taking place behind the scenes. Parker coordinated outreach efforts with the local chamber of commerce, organized with the HPO and the Department of Commerce, and worked to reach the possible investors.

The versatility of this Showcase mold was proven in the differing makeup of the issue between locations. Though the subject matter and end goals were consistent, the first event hoped to address a backlog in construction opportunities, while the second honed in more on the fearful investor. “They think there is so much red tape to it,” Parker said of the prospective buyers. “But seeing the different projects, the flip of the projects that have taken place, and then being able to hear the numbers and how they work for the projects—that helped out tremendously.”

The versatility of this Showcase mold was proven in the differing makeup of the issue between locations. Though the subject matter and end goals were consistent, the first event hoped to address a backlog in construction opportunities, while the second honed in more on the fearful investor. “They think there is so much red tape to it,” Parker said of the prospective buyers. “But seeing the different projects, the flip of the projects that have taken place, and then being able to hear the numbers and how they work for the projects—that helped out tremendously.”

Like with Elizabeth City, the results were impressive. Nine properties were slated to be showcased, and two went under contract in the lead-up to the event; their purchase was actually announced that exact day. Another property that was showcased sold within two weeks. Those buyers then bought a second neighboring building a short time after, and three other properties have significant interest, according to Parker.

“I went into it with the idea, if we could just turn one property, that was success for us,” Parker said. “It’s definitely proved to be more successful than what we thought that it would be. Anything that came out of it was worth the time and the effort and the little bit of money that we put into it.”

Momentum, and What’s Next

From its inception, the Historic Preservation Tax Credit has been an undisputed success, despite the uncertainties that surround it for new participants. The program was created in 1976, then expanded in 1998, and since that expansion, it has assisted more than 3,000 projects that have expended by private investors an estimated $2.7 billion.

These projects have a real, on-the-ground impact. Between blight and benefit, Elizabeth City and Tarboro are now enjoying the latter.

“It’s not really about even what it’s going to be. It’s about an atmosphere and creating an experience for people,” Malenfant said. “I’ve seen a huge, huge rise in the pride in downtown. Some people had kind of written it off as no longer relevant. Now there are people saying, ‘Oh my gosh, I wish I had purchased the building in downtown. I wish I had been part of this renaissance.’”

The showcases have pushed the line of that interest in preservation and rehabilitation even further, and Bartos hopes that they can continue to impact communities that may have struggled with vacant buildings for years or decades. Had COVID-19 not struck, more of these events would have taken place across the state, she says.

They’re looking to officially relaunch the Historic Building Showcases in summer 2021, pandemic permitting.

“The enthusiasm from Elizabeth City and Tarboro was just off the charts,” Bartos said. “Those were both really great days.”